Artiste-professeur invité

2016 - 2017

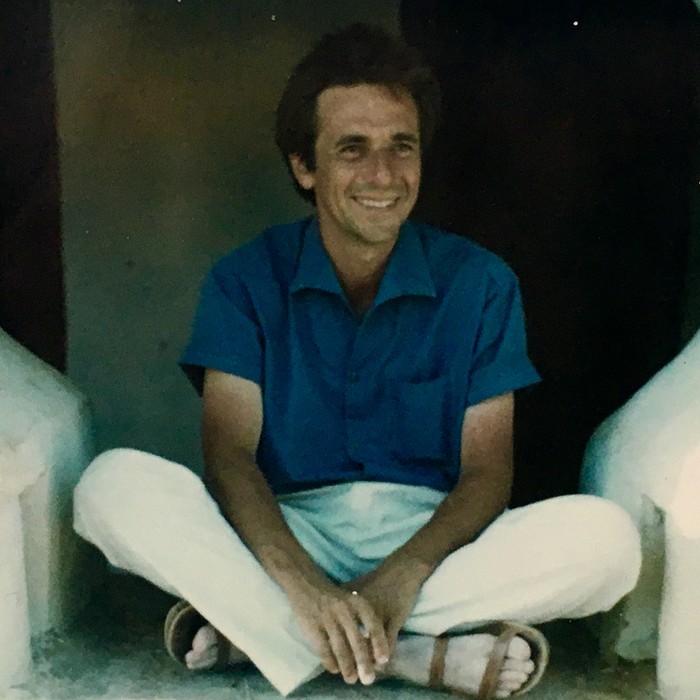

Bruno Nuytten

Born in 1945 in Melun (France)

Image section at INSAS, Brussels

BTS Image (France)

After working on a number of alternative films, first cameraman on numerous medium and short films.

Between 1969 and 1985, lighting cameraman on some thirty feature films with Bertrand Blier, Marguerite Duras, Benoît Jacquot, André Téchiné, Claude Miller, Alain Fleischer, Gérard Zingg, Jacques Doillon, Andrzej Zulawski, Alain Corneau, Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais, Claude Berri etc.

As a director, from 1987 to 1998 three feature films for theatrical release (Camille Claudel, Albert souffre, Passionnément) and in 2001 Jim, la nuit for Arte (cultural channel)

Teaching: "Image" at lNSAS, head of the "Image" department at FEMIS, and common projects supervisor at CNSAD-FEMIS.

Late September, 2001: it is still very hot in Vladivostok. Not far from the Versailles Hotel, on the shore of the Sea of Japan, the beach is like a waste ground. Here and there a few tattered parasols. In the street the girls are tall, proud of their long legs, and wear miniskirts. They are blond, their features Asian. It's a new school year. In the harbour, children with backpacks emerge from old warships lying on their side and transformed into "leaning" apartments. Minus thirty in winter: it must be freezing in there. I have an appointment at the circus with the last polar bear tamer (the others all got eaten). I'm looking for a few rather specific shots of an angry bear for a special effect in Jim, la nuit, the film I'm making for Arte.

The man is magnificent. A deeply tanned Ukrainian, about fifty years old. The circus is in concrete, rundown, even though it's the big circus in this city, and this is a place where people love the circus. In the ring, frozen by an antediluvian compressor, the polar bears, fitted with ice skates, are performing figures. Amazing. Around them, to protect us, a big net has been rigged up, using whatever was to hand. At the back, along a bar recuperated from over in the harbour, they have hung a sheet in some indefinite blue colour (for the special effects). We've got to do this quickly. The animal, a big she-bear nearly three metres tall, is trained for skating, not movies. Behind the mesh of the netting I am too high up and too far away, it's impossible to get a proper image. I need the animal to be above me, with me at its feet. The trainer accepts and suggests that I set up the camera on the edge of the ice, in the passage set aside for the bear, between its cage and the ring. The man is out there in the middle of the ice rink with only a little stick to protect him. They let the monster in. It rushes towards the ice, knocking the camera and enveloping us, my assistant and myself, in its thick fur. We have to film. We'll think about the danger later. Then something strange happens. I simply can't press the release button. I don't want to. The situation is so powerful, so rich, that the shots I want to seem ridiculously trivial. My assistant presses the release for me.

These will be my last movie shots. The first difficulties arose twenty days earlier, on the eleventh. We were shooting on a container ship heading north. During the break, in the officers' wardroom, a TV screen was showing images distorted by bad reception. The commentary was in Icelandic, and between two screens of fuzz you saw what looked like New York, some badly made disaster movie, with sequences that were too long, repeated over and over. It took a while, but it was the stunned response of the Icelandic sailors that made us realise that New York really was collapsing. No image would ever be more powerful, more mysterious or more fictional than that.

My desire to film had just taken its first knock, and the effect, much to my surprise, was emancipatory. I could see. At last: see!